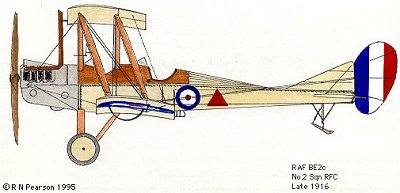

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c:

Historical Notes:

The early B.E. 2 models appeared just before the war started in 1912. Early versions were powered by the 70hp Renault engine, but there was little standardization at first. Furthermore, early versions were often used for early aircraft research, and this was carried on throughout the war with the B.E.2c machines, designated "X" aircraft, in various flight tests and experiments. One such person who experimented on the early B.E. models was Edward T. Busk, who trained as a pilot under the watchful care of Geoffrey de Havilland. Once having been trained as a pilot, Busk began a series of experiments with the B.E. aircraft, pushing them well beyond normal controllability and endurance, in order to develop an inherently stable machine for reconnaissance purposes. From Busk's research came the first prototype of what was to become the famed B.E.2c. Busk would continue his research on B.E.2cs, and would subsequently lose his life in a tragic accident in November of 1914 when the plane he was flying burst into flames over Laffans Plain.

The B.E.2c was a visionary aircraft in many ways, incorporating what was to become standard construction concepts. It had a twin spar two-bay wing construction and wire-braced box girder fuselage. The wings were heavily braced with lifting and landing wires, which would later prove to be a major obstacle to the effectiveness of the observer-gunner. Earlier models also had a landing skid as part of the undercarriage, in an effort to curtail tendencies of pilots to nose the aircraft into the ground on landing. With war imminent, the British government decided to order the B.E.2c in quantity. After some delays and repeated modifications, the first machines were produced, and the first models began to operate in France by March of 1915, yet with only thirteen available at the time.

Deliveries accelerated in the spring of 1915, with the RAF 1a 105hp engine now as standard. B.E.2c activity accelerated, with the plane being used for extensive reconnaissance duties, some bombing attacks, and even occasional pursuit of enemy recon machines. One of the more publicized actions was the attack by then Lt. Lanoe Hawker on Zeppelin sheds at Gontrode on Apr. 19, 1915. But a serious threat to the B.E. machines developed with the appearance of the Fokker Eindecker, armed with a machine gun firing through the airscrew, by late summer of 1915. It was then that the weaknesses of the B.E.2c became painfully apparent.

First, was the inherent stability of the machine itself. When flown, the B.E.2c actually resisted changes in flight attitude. This made it easy to fly, but also meant it was a difficult machine to push into maneuvers. B.E.2cs could perform such maneuvers as a snap turn, and even do this maneuver in 13.5 seconds. However, the initial half roll of the plane took two seconds (simply to position the wings perpendicular to the ground), while the plane's weight and low power caused it to lose hundreds of feet quickly when performing such a move. Furthermore, a snap turn was essentially useless, since the positioning of the aircraft's armament prevented any real use, offensively or defensively, highlighting the second problem.

The machine gun armament was placed in the forward crew position, with fixed mounts on either side. Not only did the observer have to pull the Lewis gun from one mount, and place it in the next in order to fire on enemy aircraft on the opposite side, he also had to contend with the full array of struts and wires around his position. It does appear difficult to understand why such an arrangement was designed, but one must remember that except for a few visionaries, few foresaw the possibilities of aerial combat. Moreover, there was no interrupter gear available to the Royal Flying Corps at this time, even though one had been developed in Britain privately just prior to the start of the war.

Regarding this interrupter device, it is worth noting that the design was purchased by the British government, and then promptly suppressed. The evidence available strongly suggests that since the device had been developed by a private individual, and not a government agency or contractor (such as the Royal Aircraft Factory, which had a monopolistic lock on government aircraft contracts at the time), there was no desire to use it since it would mean profits accruing to such a private individual and not someone associated with the government. In this case, elements within the British government would bear a heavy responsibility for placing many of their airmen at a serious disadvantage during the early stages of the war simply because of a statist worldview.

Aircrews desperately attempted to eliminate such deficiencies with a variety of field expedients. One example involved a pilot attempting to entangle a lead weight dangling from a string into the airscrew of an enemy machine. Possibly the most successful at the time bears a strange name... the name of its inventor, Capt. L.A. Strange. The "Strange Mount," as it was called, consisted of a Lewis gun mounted on the fuselage side near the cockpit, with the muzzle pointed outward in order to clear the propellor. In this configuration, the pilot had to crab his plane, what is now referred to as uncoordinated flying, to fire on a target. Yet despite these expedients, B.E.2cs could not operate over German lines without increasingly heavy escort from other machines as the war dragged on.

Nevertheless, B.E.2cs saw extensive service through most of the war, and in all theaters of operation. Some were slated to operate in South Africa and the Namibian desert, but were damaged on transit and did not take part in that operation. However, another group did operate in German East Africa, performing extensive long range reconnaissance patrols. One crew even carried extra containers of fuel in the cockpit, refilling the main fuel tank as they conducted their observation missions, in order to remain longer aloft.

B.E.2cs and her sister machines were also employed as anti-zeppelin night fighters, and in this configuration the aircraft excelled. Stable and easy to fly, and equipped with an upward firing Lewis gun, B.E.2cs relegated to such work downed five German airships. They were also employed in a night role against German bombers until the appearance of the Gotha machines, especially the later models with the downward and rearward firing machine gun.

Unfortunately, B.E.2cs rarely receive credit for the valuable work they performed. The bad reputation the machine received, along with her sisters, should really be directed to the British government, which appeared more concerned about protecting the Royal Aircraft Factory's government granted monopoly of aircraft production than in producing machines capable of fighting an aerial conflict. One must keep in mind that when the first B.E. planes were developed, powered flight was less than ten years old, with an industrial base not much different technologically from that of the late 1800s. From this perspective, the B.E. series aircraft were truly remarkable machines, having to suffer the indignity of soldiering on, crewed by brave men, long after the design was obsolete in a rapidly changing world.

Basic performance statistics: RAF B.E.2c

Engine: 105hp RAF 1a or 1b; various other engine configurations as well

Weight: empty 1,370 lbs; loaded: 2,142 lbs

Maximum speed: 72 mph at 6,500 feet; 69 mph at 10,000 feet

Climb rate: to 6,500 feet.... 20 min; to 10,000 feet... 45 min 15 sec.

Service ceiling: 10,000 feet; later models to 12,500 feet

Flight endurance: 3.25 hours

Basic Specifications of B.E.2c model:

Manufacturer: Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, Hants.; numerous other sub-contractors.

Dimensions: Span 37 ft; Length 27 ft, 3 in; Height: 11 ft, 1.5 in

Areas: Wings 371 sq ft

Fuel: 32 gallons; 3 gallons of oil.

Armament: varied widely, from none, to four Lewis guns. Typical recon duty was single Lewis gun in front crew position.

Primary sources: "French Aircraft of the First World War," Davilla and Soltan; "Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War I, 1919 (1990 reprint); "British Aeroplanes, 1914-1918," J.M. Bruce; "German Aircraft of the First World War," Gray and Thetford; "German Air Power in World War I," Morrow; "Aircraft vs Aircraft," Franks; "Who Downed the Aces in WWI?" Franks; "Aircraft Camouflage and Markings 1907-1954," Robertson et al; "Military Small Arms of the 20th Century," Hogg and Weeks.

Fighting and winning in the B.E.2c:

In the early part of the war, the B.E.2c is not totally outclassed by enemy scouts. Use altitude and position yourself at right angles to enemy attack. You don't have a defensive armament in the Ritterorden version, so don't worry about getting an enemy behind you to shoot at him. Instead, force him to attack at right angles. If the enemy pilot is unskilled, he will often attempt to turn back quickly for another attack using a snap turn. As a result, he will continue to lose altitude. When an enemy makes his attack and passes you, turn to follow him, keeping the distance as tight as possible. This will prevent him from taking distant shots at you even though you have an altitude edge.